Alec Egan: The Study

Charles Moffett is pleased to present The Study, a solo presentation of 16 new works that comprise the latest installment of Alec Egan's (b. 1984, Los Angeles) ongoing construction of a fictional house-and psychological exploration of its absent homeowner.

Charles Moffett is pleased to present The Study, a solo presentation of 16 new works (11 oil paintings and 5 sculptures) that comprise the latest installment of Alec Egan's (b. 1984, Los Angeles) ongoing construction of a fictional house-and psychological exploration of its absent homeowner. Since 2017, each sequential series has focused on a singular room of the house, gradually revealing more narrative clues about its hypothetical inhabitant. The new presentation depicts the homeowner's study or home office; an intimate look at their psyche and day-to-day. To that end, while the exhibition's title refers most literally to the depicted location within the fictional home, it also serves as a double entendre since the work is a character study of the individual.

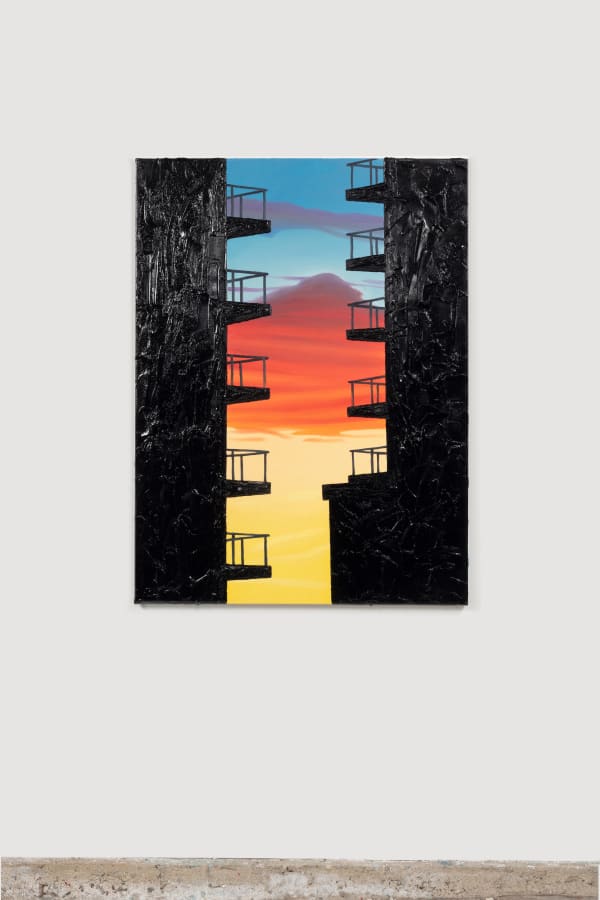

While Egan's presentations have previously consisted solely of oil paintings, The Study further brings the viewer into an immersive space through the novel integration of custom wallpaper and flooring (which matches the wallpaper and flooring in the paintings, offering the illusion of the canvasses continuing onto the gallery walls though punctuated by frames). The exhibition will also debut Egan's first-ever sculptures, which present as artifact-like possessions of the absent homeowner.

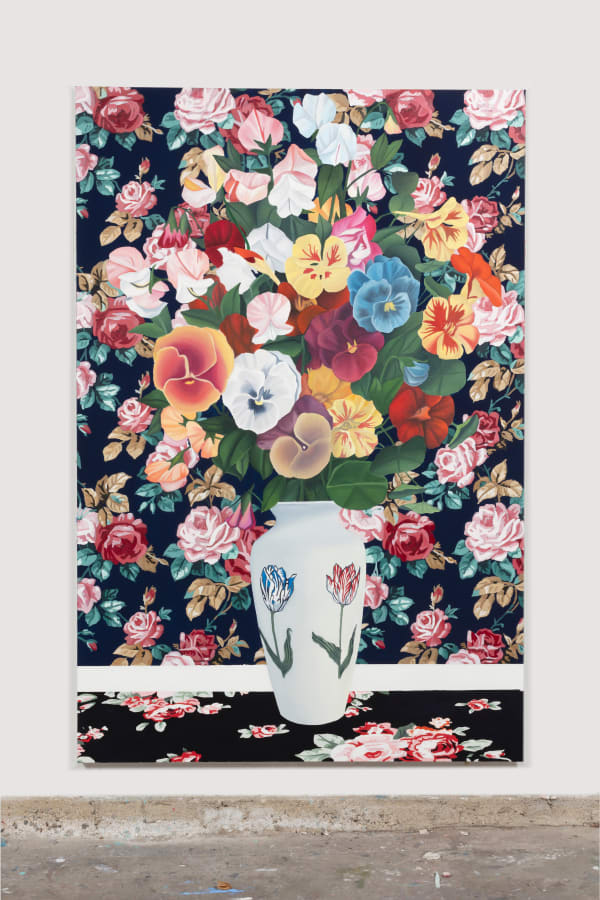

The signature aspect of Egan's painting practice is intricate floral wallpaper. He is fascinated by this type of wallpaper on several levels.

Most fundamentally, he thinks its objectively quite bizarre to cover an entire room in illustrated florals, yet wallpaper featuring patterned renderings of flowers is a mundane mainstay of décor throughout history. Which ties to another aspect of his fascination: that floral wallpaper is so intergenerational, cyclically going in and out of fashion, often impossible to definitively pin to a specific era. Egan elaborates:

"People weren't content that flowers just grew in the wild. So they had to cut them down and plant them in gardens. And they didn't think that was good enough. So they had to cut them and put them inside their homes, and that wasn't even good enough. So they had to replicate them and put them on their walls, on all of their belongings. It blows my mind a bit." This concept is most literally explored in works such as Flowers on Flowers (which depicts a sumptuous floral arrangement in a vase that's decorated with cartoon-y flowers), and Pansy Pillow with Pansy (which features an almost-pixelated-seeming needlepoint throw pillow with a floral pattern).

Overall, Egan believes that floral wallpaper has the capacity to evoke an ambiguous nostalgia of domestic environments-a psychological effect that he intends to be overwhelmingly heightened for viewers of The Study, by way of the gallery walls and floors being covered in floral patterning to such an over-the-top extent.

Egan, who prior to his painting MFA received a bachelor's degree in creative writing with a focus on poetry, approaches his painting practice with the conceptual sensibility of a poet. He is particularly intrigued by motifs and repetition, an interest that manifests in what he describes as an "ad nauseam" approach to painting; there's the obvious visual motif of flowers, but also what Egan describes as "a visual language, on top of a cultural language, on top of the narrative of the paintings. It's about pointing to everything multiple times."

Many of Egan's paintings open-endedly contextualize objects to suggest traits about the absent homeowner. For instance, in Jaws, Sandwich, and Clementine on Carpet, the implied scene in front of us is a point-of-view frame of someone seated on a floral carpet reading a book about sharks, prepared to eat a meal consisting of a sandwich and an orange. "To walk into someone's house and see this scene, you might think this person is a bit of a psycho," said Egan. Sometimes the suggestion is playful, while other times quite sinister.

An Incident is Egan's first time depicting a scene that so unambiguously presents as an "emergency," with an off-the-hook phone next to a broken wine bottle. Anchored and tamed by the saccharine floral wallpaper and rug-and presented adjacently to relatively innocuous implied scenarios like the book and sandwich-the scene isolates itself as a discrete aspect of a more complex character study.

The visual framework of Egan's practice-domestic environments-allows him to comfortably explore themes and allegories in a manner traditional to the art historical canon of still life painting, though naturally in his own style. In Dog Under Ocean Painting, we have a painting of a painting. It's in compositional dialogue with a dog, which Egan based on a puppy photo of a real-life dog who is now 16 years old. It speaks to mortality, among other themes:

"The ocean here is painted neither in motion (storm or wind) nor near land. The gaze of the dog and the gaze of this mild ocean scene both suggest the abyss, the existential, the weight of time staring back. To irreverently reference the famous Nietzsche quote: 'For when you gaze too long into the abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.' So it's these mundane things that were quaintly adorn our lives with to distract us from reality, like pets and landscape paintings, that become our gravest markers of mortality."

"The whole concept of the rooms makes me feel an extraordinary amount of existential dread sometimes," Egan reflects. "The ornamentals-on-steroids effect of the scenes calls into question what we are, and what we value in our human experience. It becomes very psychological. The repetition of everything could drive you crazy."